Information is displayed in multiple columns:

Memory monitor firefox code#

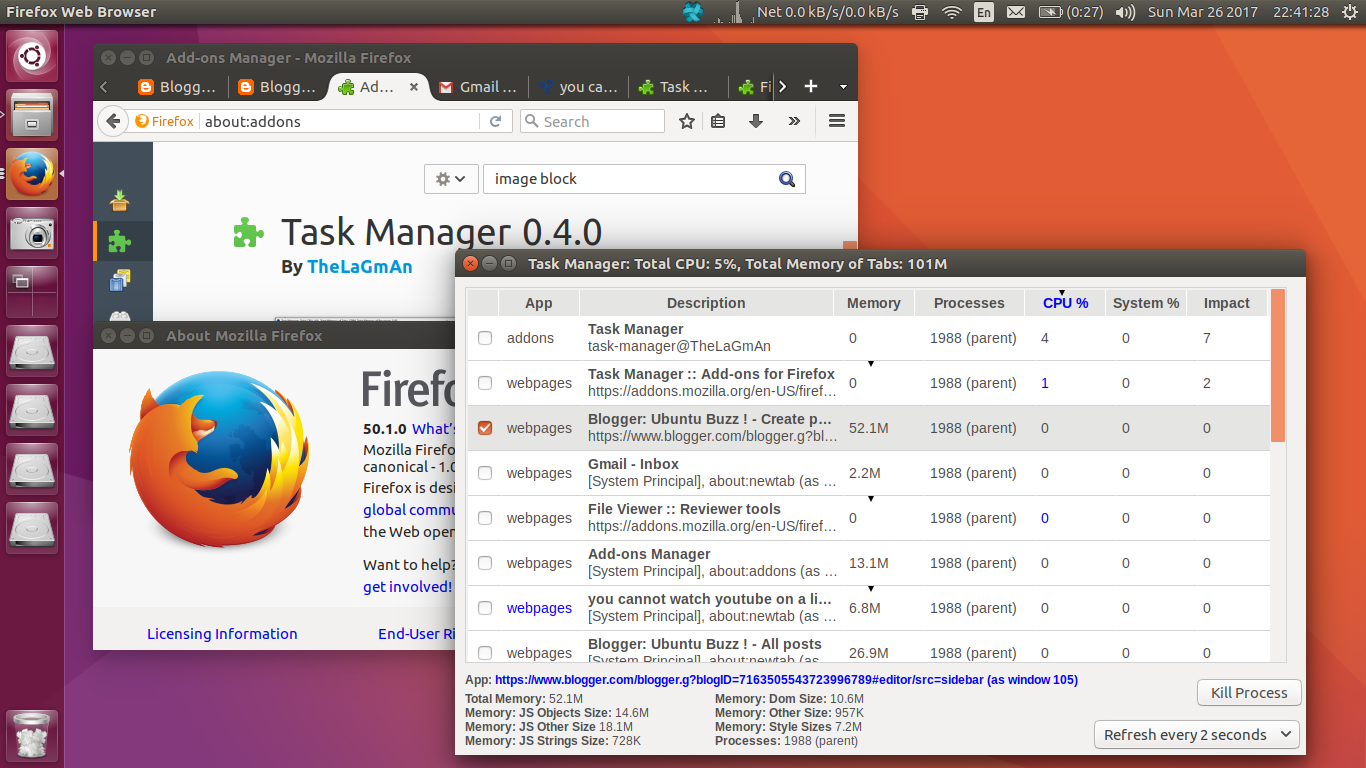

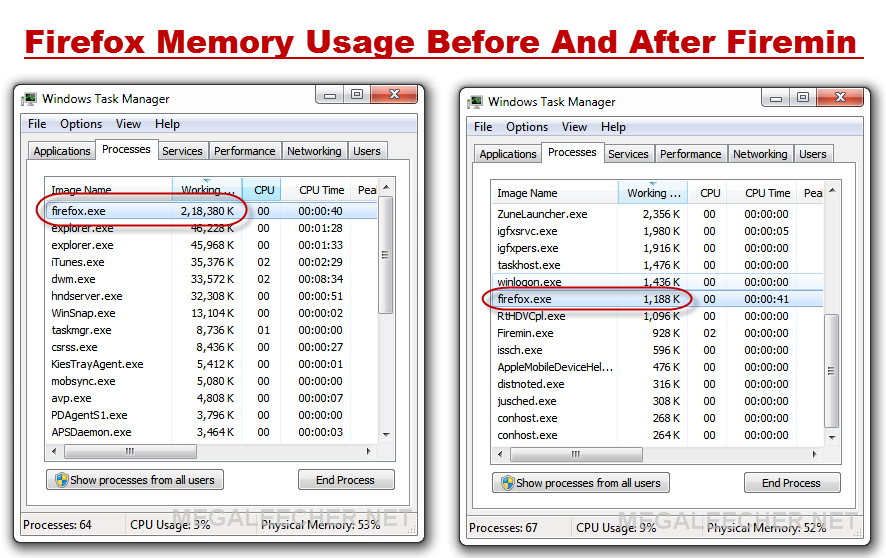

The output of a PowerShell code displaying the memory use for the Microsoft Edge browser.Tip: You can also enter about:processes in the address bar or use the keyboard shortcut Shift + Esc to open this page. The results of these test cases shouldn't dictate which browsers an organization prefers or even allows their users to run, but it can provide insight into how browsers consume this resource to inform decision-making (Figures 2, 3 and 4). Google Chrome has accompanying crash handler processes that are not included in these metrics.

Memory monitor firefox Pc#

The Safari browser was excluded from this test because Apple has not released a PC version of Safari since 2015 and that version is no longer available for download.īelow are the process names associated with each browser in PowerShell.

Administrators should use the PowerShell code listed above to report on each browser's memory use. The parameters of this test case are a single open browser tab. This case study covers Microsoft Edge, Google Chrome and Mozilla Firefox, all running on a virtual machine. Comparing memory use across browsersĮach browser uses memory in a different way, so administrators can't truly get a feel for a browser's memory usage by simply looking at a single webpage or even a few different webpages.ĭespite this, a simple test can illustrate the point that browsers use memory in different ways and to different degrees. As an alternative, admins could use /1GB to display the memory use in gigabytes.

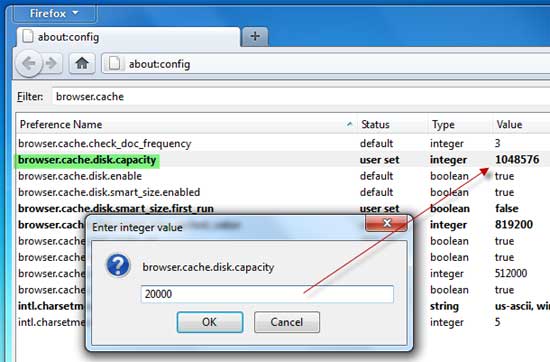

Without the /1MB portion of the command, the working set memory will be displayed in kilobytes. The last line of code displays the total working set memory consumed by the browser while converting the value into megabytes. To learn how many processes the browser is using at the moment, just enter $B. This allows the working set memory used by each of the MSEdge processes to be added together, giving the admin the total amount of memory that the browser is consuming across all of the open tabs. The administrator should then pipe this information into the Measure-Object cmdlet and append the Sum parameter. This variable is called $B and it points to the working set memory usage of the process in question (Figure 1). This second line of code measures browser memory use by creating another variable. PowerShell can display all of the individual browser processes and the memory that they are consuming. If an administrator wants to see the individual processes that are referenced within the $A variable and the working set memory consumed by each process, they can enter the $A | Select-Object Name, WS command.

Incidentally, the trick to making this code work with other browsers is to substitute the process name for the desired browser. The first line of code creates a variable named $A and associates that variable with all of the running processes named MSEdge. The three lines of code report the memory usage for the Edge browser to show an example of one such PowerShell inquiry: $A = Get-Process | Where-Object One way the admin can assess a browser's overall memory use is to use PowerShell to examine the processes associated with the browser. To measure a browser's overall memory use, an administrator must collectively examine all of the browser's processes. There may also be processes tied to other browser functions in the background. This is because each browser tab is linked to a separate process and each process has its own memory use. Measuring the amount of memory that a browser is consuming isn't quite as straightforward as it may seem. Each of these individual processes consumes memory, which can add up quickly. These processes allow for parallel instruction execution, boosting the browser's performance. Modern browsers are multithreaded and therefore use multiple system processes. As such, browsers use memory when performing the various computations that are involved in rendering webpages. As such, using a memory cache greatly improves a browser's performance.Īdditionally, browsers rarely render static HTML on a page. Although browsers still cache objects to disk, just as they always have, memory caches are faster than disk caches. Web browsers use memory to cache the various elements that make up a webpage.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)